Game designers make better comic writers than novelists for a few reasons - first, aside from maybe Hideo Kojima and the Metal Gear Solid series, game designers must condense their output to fit into set constraints. If I work on a mobile phone game, I've only a few kilobytes-worth of text I can squeeze in, and then there's that tiny screen! Instead of saying "When you pick up the basketball, run towards the basket", one must instead say "Pick up ball, run to basket".

Conversely, when you write a novel, your first instinct is to describe in detail. You set the scene with words, and you have to cater to your entire audience on the first try – as Jef Mallett said, “Being a good writer means never having to say ‘I guess you had to be there’.” This is doubly important with fantasy stories because you – the writer – are the only person who’s ever been to the place you’re describing. With a comic, words take a backseat. Description is no longer imperative, as the artist can show exactly what it is you mean to say.

In this respect, writing a comic script is a bit like writing text for a game. Both comics and games rely on visuals to tell the story, with text acting as a supplement. Crack open any good comic and you’ll see the art is telling the story most of the time – not the text. Because of this, finding the right balance between what you want the characters to say and what you want the characters’ actions to say is a blurry line that I’m still figuring out. As I’ve learned over the last few drafts of the script, when you write a comic, the artist is as much a writer as the writer is. If you believe a picture is worth a thousand words, then that makes the artist even more a writer than the actual writer!

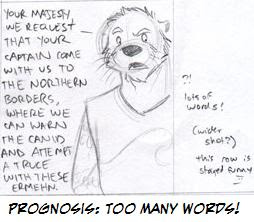

My first draft of the Four Kingdoms script was very much still the novel I had begun to write beforehand. It wasn’t until Rachel laid out the initial thumbnails of the Felis prologue and some of the other scenes that I realized I needed to apply my game designer shtick to the comic’s script. Let’s take a look at the evolution of some scripty bits:

The Lost "Felis Prologue":

In the original prologue, a group of shadowy hooded figures argue around a table in a dusty old library. After some back and forth, a few plot details began to emerge – they were recording some important historical event, a stranger was among them who had been a participant, and the facts surrounding this event were impossible to determine. The scene would have gone on for about two and a half pages, most of it just people sitting around a table arguing.

A snippet of this lost scene:

Shadow 1: This is not another one of your abridged travesties! This is the most important thing that any of us in this room will ever write! There hasn’t been an event like this since the Four Kingdoms War, and that was a lifetime ago!

Shadow 2 (to the others): Brother Camriel is speaking in exaggerations.

Shadow 1: I speak the truth! Our writing of these events will affect our relations with all the races of the Four Kingdoms. This is not some skirmish between Vulpin tribes or Polcan pirates! We write of a world war, and we cannot take that responsibility lightly!

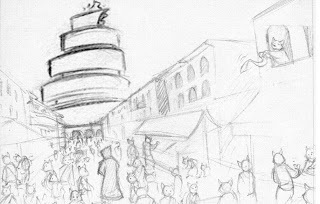

Words and words and words! For a comic, especially a comic that introduces a brand new fantasy world, showing a bunch of shadowy cloaked characters in a library probably isn’t the best way to garner interest. Thankfully we came to our senses and condensed the Scholars sequence into a single page and added some nice visual splendor to pique interest.

My second and last example (since I’m starting to belie my point about being succinct with this post) is a series of panels from Quinlan’s introduction:

Original text:

Quinlan: When my grandfather told me that I needed to join the Tamian Military, he gave me a choice of paths to follow. I chose to be a scout so I wouldn’t have to kill anyone. He was against it, of course. It was the first time we ever really fought.

Janik (surprised): Yeah, but… you’re so good at Tesque…

(Quin collects his supplies and stands up, offering Janik a paw)

Quinlan: Knowing how to fight is a philosophy. The true act of fighting, though, that’s… something quite different. Honestly, I don’t know whether to thank my grandfather or hate him.

Janik: Why’s that?

Quinlan: Well… it’s hard to explain. To him, the best way a warrior’s life could be spent was by constant fighting, risking life and limb. Whenever he tried to explain it to me, I just got… scared. Eventually he stopped trying to explain, and he let me become a scout. I think he considered that his greatest failure.

Janik: And you think that’s why he willed you to become captain after he died?

Quinlan: How could I turn down his dying wish? He got what he wanted, that’s all he cares about, I’m sure.

Janik: Well, he lived in a violent time. Things are more civilized now.

Quinlan (as he and Janik walk away): That’s just what worries me, Janik… I don’t think that’s true. I don’t think that’s true at all.

And now the scene as it appears in a more current draft:

So, getting back to my original point – if you’re a novelist at heart, comic writing will take quite a bit of practice to get right. If you’re a game designer, especially a game designer that constantly has to work within tight size constraints – you might actually want to give comic writing a whirl. Half of the fun of game design comes from working within constraints - so the constraints of comic writing should very much appeal to you.